Our friend and colleague Lamet is a clinical officer in the Church of Uganda Hospital in Mukono, a township a few miles outside Kampala. He thought this story worth sharing: we think he’s right!

Here is his account.

Suleiman, just 8 years old, lived with a disabling illness for 6 years until Mukono Church of Uganda Hospital (MCOUH) with Jamie’s Fund offered him a new life. His mother lights up with much joy as she looks back and the realisation of how her son’s life has been changed for the best.

Their story

Teopista and Henry, Suleiman’s parents, are peasant farmers in a rural remote area of Uganda. They could barely afford any resources to save the life of their child.

They were blindfolded by their traditional beliefs into accepting that Suleiman’s situation was permanent, not knowing that this was an illness that could be treated.

“Suleiman has been a survivor and strong fighter. I have had nine children, five of whom have passed on, leaving me with four”, his mother says.

Teopista goes on to say in agony that her son had been born at home instead of in hospital because the closest health facility was 75km away.

At the tender age of two, Suleiman started experiencing a lot of painful attacks characterised by loss of consciousness and stiffness of the body. The attacks became more frequent every now and then and began to endanger Suleiman’s life.

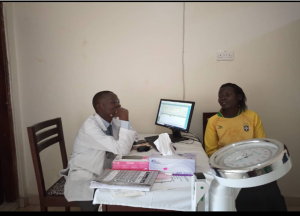

Teopista, Suleiman’s mother giving history about the son’s illness

This illness is known as “Ensimbu” by local people, and associated with evil spirits. Suleiman’s parents first ignored it until he turned three years.

Teopista says, “The village elders advised us that the only way we could get our son healed was to please the ancestors through making sacrifices because this illness was a sign that they are unhappy about us.”

This condition was assumed to be a curse on their family and so they continued seeking ancestral guidance and healing through sacrifices for the following 4 years. But there was no improvement but rather increased severity of the attacks.

” My son was increasingly deteriorating both mentally and physically, thus I gave up”

At the age of 8, even though Suleiman’s condition had not resolved, his mother tried to enrol him into a nearby private school so that he could at least learn how to write his name and to read a few little things.

However, this became expensive, and most of Teopista’s income was coming just from her small garden. There was no help from her husband whose only work then was drinking alcohol from morning to sunset.

While at school, Suleiman’s major challenge was stigma from both the teachers and his fellow learners. They kept on laughing and calling him unpleasant names like “possession child”. They would not associate with him because they thought that his illness could spread to them.

After just a month, Suleiman had a terrible attack while at school that almost cost his life. He spent about 4 hours unconscious. “The next day, he refused to go back to school mainly because of the insults and humiliation” mother said.

The turning point

“It was a Sunday around 9:30 am. A team from MCOUH visited our church to health educate us about mental health services at the hospital.” Teopista reports.

She added “I seldom went with my son to church due to fear of embarrassment, but that day I was the happiest person to receive such information, I was so humbled and will never forget that day in my life”

Teopista says that day the light of hope dawned in her family.

At the hospital

Lamet takes up the story: “It was a Friday morning; I saw a worried, humble woman holding a very weak child in her hands. The child had a big scar on the right leg. I found out later on that he had at one time fallen into the fire in their home.”

On thorough assessment, Suleiman had long been battling with epilepsy. Unfortunately, in the middle of the interview he went into ‘status epilepticus’, and the fits kept coming continuously. He was reported to have had multiple attacks over the previous days.”

On thorough assessment, Suleiman had long been battling with epilepsy. Unfortunately, in the middle of the interview he went into ‘status epilepticus’, and the fits kept coming continuously. He was reported to have had multiple attacks over the previous days.”

I admitted Suleiman, and as we managed the seizures, so he stabilized.”

“Whenever I reviewed this child on the ward, the mother would say “The rest of my hope lies here” and this statement made me reflect and think more deeply of how much this family had suffered with this illness.

Three days later, Suleiman was discharged home after being initiated on treatment and a review date was set. Mother left the hospital very happy.

On the second visit

Teopista never gave up fighting for her son’s life and not at any time did she think of doubting the team that was working on her son.

Suleiman had had just one single attack in a month while on treatment. This was amazing to both mother and son.

“My son’s dream of continuing with education has been reborn ” she said. Suleiman could not stop telling his mother of how he wants to become a doctor.

The new changed life of Suleiman is worth celebrating

Suleiman is attending the mental health clinic at MCOUH every first Friday of the new month. He has shown great improvement on treatment and is cooperating very well with taking the medication.

He has been re-enrolled back to school and has started his first year in a nearby school. The family is so grateful for the services supported by Jamie’s fund at MCOUH.

Every single day, we get children like Suleiman who have long been battling silently with their own lives to fit into society, especially because of the stigma associated with the illness they bear.

Thanks to Jamie’s Fund

You will probably know those friends who are perpetually there for you any time you need them. They easily sense when you need them and immediately engulf around you and turn your worst nightmares into big smiles.

It is the reason we shall continue to be most grateful to our partners – Jamie’s Fund – for supporting the mental health of our dearest communities.

Lamet Jawotho

Clinical Officer

Mukono Church of Uganda Hospital

If you would like to contribute to the work Jamie’s Fund is doing in Uganda, please click on the Donate button above.

Maliba Outreach Clinic and the contribution of Psychiatric Clinical Officers

/in News, Uncategorised /by Jenny SmithIn mid-March, just before the Covid 19 internal travel restrictions were imposed in Uganda, the mental health team from Kagando Hospital went out by motorbike to hold an outreach clinic at Maliba, about 25 miles away. Joseph, the Psychiatric Clinical Officer (PCO) led the clinic, Rachel, one of the regular MH nurses was helping, and Bisiah, a newly qualified PCO, volunteered to gain experience.

Between them, they saw and treated over 70 local people with epilepsy and psychosis. Some 55 of these were expected returnees, and the rest, although less reliable attenders, were mostly somewhat familiar to the staff. As mental healthcare services based at hospitals such as Kagando, Bwindi and Kisiizi have established themselves and grown over time, one of the important things they do, is to maintain vulnerable people on treatment, keeping them well and productive in their communities.

Psychiatric Clinical Officers are usually the leaders of mental health services in Uganda. They work at a level between experienced nurses and junior doctors, having undergone a three-year training in the management of mental illness. Jamie’s Fund is sponsoring the training of more PCOs, to enable hospitals without staff trained in psychiatry to develop one of their own staff as a mental health service leader and so develop mental health services at their hospital. This is a real partnership, as Jamie’s Fund meets the fees and other immediate costs of the training, while the hospital continues to pay the trainee’s salary, and bonds that person to return to work there for a period of time after qualification.

We have 3 individuals training currently at the PCO School at Butabika in Kampala. Many more are needed as most hospitals don’t have a PCO. The current cost met by Jamie’s Fund is about £1,300 per person each year. Could you, your organisation, your family, or a group of friends sponsor one person for one year’s training, or see them through to qualification as a PCO over the three years? Please get in touch if you would like to discuss this further.

Linda Shuttleworth

Health Care Challenges

/in News, Uncategorised /by Jenny SmithAs much of the world has been engaged in coping with the Covid 19 pandemic, we have been keeping in touch with our partner hospitals in Uganda. We were keen to understand the challenges they have been facing, and how they have been responding. Towards the end of May, we contacted all our active partners, and soon had replies from nearly half of them.

Empty waiting rooms

All hospitals have faced reduced income, because their training schools have been closed, and fewer patients are coming for treatment. In some cases, numbers attending are 25% of what they were. The barriers for patients are lack of money and lack of transport as public transport had been banned for some time, only now beginning to be allowed again, with increased spacing.

The hospitals have the frustration of seeing drugs in their pharmacy being wasted as they go past their expiry dates.

Mental ill health is on the increase, not only because people are unable to access treatment. Poverty and isolation can tip vulnerable people into mental ill health, as anxiety, depression, and suspicious beliefs run unchecked. And hospitals are noticing an increase in domestic and gender-based violence, drug and alcohol misuse, and teenage pregnancies.

Fewer patients

General health is suffering too, as people are less able to access child immunisation programmes and regular HIV clinics or access emergency treatment. As people delay seeking treatment in the early stages of illness, they are more often becoming severely ill and less likely to recover. The number of deaths from Covid has thankfully been low, but many people have suffered in other ways due to the virus and wider impact of the lockdown both on health and on the economy.

Despite having a fraction of the resources available to us, hospitals have done their best to respond to the crisis. They have provided transport and temporary accommodation for their staff to enable them to be at work. The mental health teams have reached out to their communities with phone calls and radio broadcasts, encouraging people to come in for treatment. They have set up informal helplines. They have gone out to bring people in who were at risk of becoming mentally unwell. And they have done their best to keep everyone safe, with social distance and available PPE.

Uganda has its Healthcare Heroes too!

Linda Shuttleworth

MENTAL HEALTH AWARENESS PROGRAMME AT KISIIZI

/in News /by Jenny SmithAn Important aspect of mental health work in Uganda, is to offer the local community an alternative understanding of mental ill health. Traditional beliefs about epilepsy and mental ill health can be unhelpful, and delay or prevent the person accessing healthcare. After all, if you believe that your child’s fits are because he or she is cursed, why would you go to the trouble and expense of taking the child to a hospital or health centre? Likewise, if your relative’s erratic thoughts and behaviour are apparently caused by witchcraft or sin, how could a clinician help? And these traditional beliefs can be very strongly held, even beyond the more isolated rural places, and by well-educated people.

Jamie’s Fund has been supporting Ugandan healthcare staff to inform local people as well as to treat them. Many of the hospitals we know have been spreading the word since the first mhGAP* training course we sponsored in 2018. Mukono Hospital just east of Kampala has reached thousands of people by giving mental health talks at local churches, straight after the services. St Stephens Hospital in Kampala has reached out to local youth among the urban poor in their catchment. Other hospitals such as Kisiizi, Bwindi and Kagando routinely deliver a community mental health message every time they arrive for an outreach clinic.

Primary school class

Georgious, the PCO (Psychiatric Clinical Officer) leading the service at Kisiizi, just sent us a report of the mental health awareness programme they started in December 2019. Between then and February, they visited 3 Primary Schools, 2 Secondary Schools and one of the churches. You can see images of some of their activities here. Travel restrictions to control the spread of Covid 19 have now halted their programme until further notice, but they have plans to resume as soon as they can.

Secondary school class

The Covid restrictions in Uganda have also put a temporary halt to Kisiizi staff holding their regular outreach clinics. But the good news is that, because staff from 5 Health Centres were included in Kisiizi’s mhGAP training rollouts, they have been able to continue to treat 35 to 45 patients every month in the outlying areas. The figures Georgious has given us show another important achievement; that the number of new patients is now small compared to the number of repeat attendances (9 new to 272 repeats); this means that people who need it are being maintained on treatment and followed up effectively. Great work Georgious and the Kisiizi mental health team!

Linda Shuttleworth

*mhGAP is the World Health Organisation programme to train non-specialist healthcare staff to recognise and treat the common presentations of mental ill health and epilepsy.

Tough times

/in News, Uncategorized /by Jenny SmithA rural road – but no-0ne on it

The Ugandan hospitals are facing hard times at the moment, as are many of the local people. The initial lockdown because of Covid was eased slightly on the 5th of May but there is still no public or private transport allowed without specific authorisation.

This makes it hard for people to get to hospitals when they are ill and there are too many disaster stories about mothers in labour not being able to reach hospital for timely interventions. Staff who live some distance from the hospitals also struggle to get there to work, or have to stay at the hospital if they can, but apart from their families.

Access to food is a problem in some places. Surveys in different African countries have shown that more than two thirds of people said they would run out of food and over half would run out of money if they have to stay at home for 14 days. The lockdown in Uganda has been longer than this already.

People in different countries are saying “It is hunger I am worried about, not the virus”

So far Uganda has done well at limiting the known number of cases of Covid and many of the rural hospitals have not seen any cases. So, you can understand the sentiment.

Because of the restrictions on transport, the hospitals we work with are not seeing anything like the numbers of patients they are set up to treat. They are also having to spend more than budgeted on hand sanitizer, PPE clothing etc. This means the hospitals are under significant financial pressure.

There is a risk that resources are being diverted from other health issues such as HIV and TB. Much progress has been made in establishing effective programmes to maintain people on their treatment, but the current restrictions make it hard for some of these programmes to operate and there is a risk that some of the progress in treatments made in the past decade will be lost.

Even a small amount of water makes roads difficult to pass

Parts of Uganda are facing other challenges. In the west, one of the hospitals we visited last year has been largely demolished by flood waters and many people have lost homes and crops. One lady said “You tell us to stay at home, but we now have no home. You tell us not to go to the market, but to work in the smallholding, but we now have no small-holding.”

In the east of Uganda and in Kenya and South Sudan there is the largest swarming of locusts there have been for many years. They devour enormous quantities of crops and vegetation, resulting in hunger.

Life in a low-income country can be tough.

Maureen Wilkinson

Looking over the Uganda border into Western Kenya

Covid 19 “Lockdown” affects many aspects of life.

/in News, Uncategorised /by Jenny SmithA village road (prior to lock down)

“Esther”, one of the three women we are sponsoring to train as a psychiatric clinical officer sent a message telling us how things aren’t working for her in Uganda.

They were sent home from the training school in Kampala when all institutions were closed by the Government. They were told that when they came back they will have to sit exams on what they would have been taught, had they been in school. They have been given the teaching notes on their computers, so they are expected to work from those.

She lives at home with her parents, some miles from the hospital. She hoped to be able to work in the hospital once she was home, but because of the ban on public transport she can’t get there. Not even the ubiquitous boda bodas, the motorbike taxis, are allowed to move.

Consequently, Esther is working with her parents on their small farm during the day, so they have some food to eat, and she studies as best she can in the evenings.

Many people in Uganda only earn enough to live on for a day or two at a time. This lockdown is causing severe problems, especially for the poorest who have no reserves.

It is possible that the lockdown will be lifted on 5th May.

Ewan Wilkinson

A life changing story of an 8-year-old is worth sharing.

/in News, Uncategorised /by Jenny SmithOur friend and colleague Lamet is a clinical officer in the Church of Uganda Hospital in Mukono, a township a few miles outside Kampala. He thought this story worth sharing: we think he’s right!

Here is his account.

Suleiman, just 8 years old, lived with a disabling illness for 6 years until Mukono Church of Uganda Hospital (MCOUH) with Jamie’s Fund offered him a new life. His mother lights up with much joy as she looks back and the realisation of how her son’s life has been changed for the best.

Their story

Teopista and Henry, Suleiman’s parents, are peasant farmers in a rural remote area of Uganda. They could barely afford any resources to save the life of their child.

They were blindfolded by their traditional beliefs into accepting that Suleiman’s situation was permanent, not knowing that this was an illness that could be treated.

“Suleiman has been a survivor and strong fighter. I have had nine children, five of whom have passed on, leaving me with four”, his mother says.

Teopista goes on to say in agony that her son had been born at home instead of in hospital because the closest health facility was 75km away.

At the tender age of two, Suleiman started experiencing a lot of painful attacks characterised by loss of consciousness and stiffness of the body. The attacks became more frequent every now and then and began to endanger Suleiman’s life.

Teopista, Suleiman’s mother giving history about the son’s illness

This illness is known as “Ensimbu” by local people, and associated with evil spirits. Suleiman’s parents first ignored it until he turned three years.

Teopista says, “The village elders advised us that the only way we could get our son healed was to please the ancestors through making sacrifices because this illness was a sign that they are unhappy about us.”

This condition was assumed to be a curse on their family and so they continued seeking ancestral guidance and healing through sacrifices for the following 4 years. But there was no improvement but rather increased severity of the attacks.

” My son was increasingly deteriorating both mentally and physically, thus I gave up”

At the age of 8, even though Suleiman’s condition had not resolved, his mother tried to enrol him into a nearby private school so that he could at least learn how to write his name and to read a few little things.

However, this became expensive, and most of Teopista’s income was coming just from her small garden. There was no help from her husband whose only work then was drinking alcohol from morning to sunset.

While at school, Suleiman’s major challenge was stigma from both the teachers and his fellow learners. They kept on laughing and calling him unpleasant names like “possession child”. They would not associate with him because they thought that his illness could spread to them.

After just a month, Suleiman had a terrible attack while at school that almost cost his life. He spent about 4 hours unconscious. “The next day, he refused to go back to school mainly because of the insults and humiliation” mother said.

The turning point

“It was a Sunday around 9:30 am. A team from MCOUH visited our church to health educate us about mental health services at the hospital.” Teopista reports.

She added “I seldom went with my son to church due to fear of embarrassment, but that day I was the happiest person to receive such information, I was so humbled and will never forget that day in my life”

Teopista says that day the light of hope dawned in her family.

At the hospital

Lamet takes up the story: “It was a Friday morning; I saw a worried, humble woman holding a very weak child in her hands. The child had a big scar on the right leg. I found out later on that he had at one time fallen into the fire in their home.”

I admitted Suleiman, and as we managed the seizures, so he stabilized.”

“Whenever I reviewed this child on the ward, the mother would say “The rest of my hope lies here” and this statement made me reflect and think more deeply of how much this family had suffered with this illness.

Three days later, Suleiman was discharged home after being initiated on treatment and a review date was set. Mother left the hospital very happy.

On the second visit

Teopista never gave up fighting for her son’s life and not at any time did she think of doubting the team that was working on her son.

Suleiman had had just one single attack in a month while on treatment. This was amazing to both mother and son.

“My son’s dream of continuing with education has been reborn ” she said. Suleiman could not stop telling his mother of how he wants to become a doctor.

The new changed life of Suleiman is worth celebrating

Suleiman is attending the mental health clinic at MCOUH every first Friday of the new month. He has shown great improvement on treatment and is cooperating very well with taking the medication.

He has been re-enrolled back to school and has started his first year in a nearby school. The family is so grateful for the services supported by Jamie’s fund at MCOUH.

Every single day, we get children like Suleiman who have long been battling silently with their own lives to fit into society, especially because of the stigma associated with the illness they bear.

Thanks to Jamie’s Fund

You will probably know those friends who are perpetually there for you any time you need them. They easily sense when you need them and immediately engulf around you and turn your worst nightmares into big smiles.

It is the reason we shall continue to be most grateful to our partners – Jamie’s Fund – for supporting the mental health of our dearest communities.

Lamet Jawotho

Clinical Officer

Mukono Church of Uganda Hospital

If you would like to contribute to the work Jamie’s Fund is doing in Uganda, please click on the Donate button above.

Covid 19 Training for Ugandan colleagues

/in News, Uncategorised /by Jenny SmithOn Good Friday, Dr Nick Bass and Edmund Koboah, from the East London NHS Trust, facilitated an online presentation and Q&A session around Covid 19, for staff from some of the health facilities we work with in Uganda.

We had invited seven of the hospitals we know to participate, but some had difficulties with getting good enough access to the internet to take part. In the event, seven staff from two hospitals “zoomed” in.

Ugandan staff learning to use PPE (from A.M.R.E.F.)

They told us that they have access to some PPE, and that they have not yet had Covid training from the Ugandan Ministry of Health, so this was timely and helpful. They had questions about managing the safety of their families and communities while looking after patients with Covid.

We were able to forward the presentation to all seven hospitals, together with some useful documents. Nick recorded the session, and we hope to find a way to send that too. Good teamwork!

We are grateful for the generosity of East London NHS Trust who offered to share their Covid 19 training which they adapted for the Ugandan mental health staff. The training was about the safe assessment and management of mental health service patients who have or may have the coronavirus.

Linda Shuttleworth

FRONTLINE MENTAL HEALTH STAFF OVERCOME COVID 19 RESTRICTIONS, THANKS TO mhGAP!

/in News, Uncategorised /by Jenny SmithPCO* Joseph Wakabi, who leads the mental health team at Kagando Hospital, often gets in touch with encouraging photos and information about the clinics they have just held in the more remote villages.

However, the Ugandan Government, like many others, last week imposed movement restrictions to try to curb the spread of the coronavirus. This means that the team is unable to continue their usual programme of outreach clinics.

But…Joseph has just told us that they have been able to send supplies of medication to the outlying Health Centres. Not only that, because a staff member from each Health Centre was trained in the course of Kagando’s mhGAP roll-out programme, the Health Centres have been able to carry on treating and caring for those with mental illness, even under lockdown.

Lake Katwe outreach

And the regular Tuesday mental health clinic at the hospital still runs as normal; 40 people came for treatment yesterday.

Great work, Joseph and the Kagando team!

*A PCO is a Psychiatric Clinical Officer; these staff usually lead mental health services in Uganda.

Kagando Hospital lies to the west of Uganda, almost on the border with Congo.

Linda Shuttleworth, JF Trustee.

KAGANDO HOSPITAL MEETS THE GROWING NEED FOR MENTAL HEALTH CARE

/in News, Uncategorised /by Jenny SmithJoseph Wakabi, a psychiatric clinical officer, and his small team of mental health staff used to hold their monthly outreach clinics at Kitabu and Kyarumba on the same day. The numbers of people coming for treatment have increased, so that now they visit Kitabu on a Monday and Kyarumba on a Thursday.

At Kitabu, patients such as James are seen at home to continue the treatment to improve their mental health. As the community begins to hear about the service, and understand more about mental ill health, and the possibilities for treatment, more families are asking for help.

This second man, newly started on treatment, has been shackled at home for more than a year, because his family did not know what else to do. these shackles are made from bent steel bar so they are on his legs permanently. Can you work out how to change his trousers – it can be done but not easily! Try and imagine living with these shackles. But with treatment we expect he will return to a more normal life and have the shackles removed with the agreement of his community

At Kyarumba Health Centre this week, 40 people were seen and treated for conditions such as psychosis and epilepsy.

Jamie’s Fund supports the work of Joseph and his colleagues, enabling them to take mental health care out to remote parts of the community where it is most needed.

Linda Shuttleworth, 13.03.2020

COVID-19 Statement by Jamie’s Fund

/in News /by EdwardLambAt the beginning of March, Jamie’s Fund was delighted to support another mhGAP* Train the Trainers course. Healthcare workers from nine hospitals were equipped with the skills to teach their clinical colleagues to identify and treat routine forms of mental ill health.

It is unfortunate that this has happened at this time when the world is closing down as a result of the Coronavirus pandemic. Although this virus seems to have been rather slower to spread to Africa than elsewhere in the world, we are beginning to see an acceleration in some places. However, governments in countries such as Uganda have used the time to implement preventative action to try to protect their citizens. In Uganda, for example, there have been measures to control and discourage the movement of people at the borders, schools and universities have been closed, and large scale social, cultural, religious and political gatherings have been suspended.

These measures will inevitably have an impact on the process of cascading the mhGap training, as further workshops will need to be delayed till life returns to more normal. Despite this, the mhGap model has proved to be a strong and effective one and we expect to resume delivery of the training soon after the present measures are eased and it is considered safe to do so. In the meantime, we continue to give our support to the frontline staff in Uganda and to wish them good health.

While our thoughts are very much with the clinicians and patients in Uganda, for us as a charity the present emergency also means that our planned visits to our partners in Uganda have been postponed until the situation improves. However, we also continue to communicate with many of friends, colleagues and partners in Uganda and we can still support them in their planning as they look to grow their mental health services. Perhaps the most important thing, though, is to give them encouragement and to let them know that they are not alone. They need this message now, especially now.

We are still able to send funds and continue to support many important initiatives as well as look at new projects and you can help. We recognise that there is a great deal of uncertainty and concern about incomes and jobs in our own country but if you are able to help, please click on the DONATE button or send messages of support which we can pass on to staff in Uganda.

Linda Shuttleworth, Trustee, Jamie’s Fund.

*mhGap is a World Health Organisation programme designed to give non-mental health clinicians, particularly in low and middle income countries, a good understanding of mental illness so that they can diagnose and treat many of the more straightforward conditions.