WHO WOULD HAVE THOUGHT IT!

A group of six trustees and volunteer clinicians visited Uganda in February, the first time this has been possible since September 2019. It was a trip full of challenges and surprises, but it was a joy to see old friends and colleagues again, and be able to share news first hand. Some of the hospitals we support have really struggled during the pandemic, due to the impact of hard extended lockdowns, as well as that of sickness and bereavement. Others have, well, surprised us!

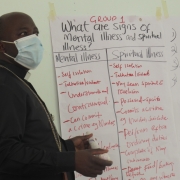

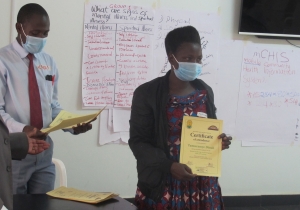

At Uganda Martyrs Hospital in Ibanda, over towards the west of the country, the response to our first visit was to take up the opportunity to send two staff to become mhGAP trainers. These two then rolled out the training to 25 general trained health staff, who have brought their mental health skills to wards, outpatients departments, and local Health Centres. They now offer regular mental health care in the hospital.

But what came out of the mhGAP training that we hadn’t expected, was a peer-supported residential mental health centre! Senior Nursing Officer Sister Flora and Certificate Mental Health Nurse Innocent hired a building nearby and set up a centre for people recovering from mental ill health! Led by Innocent and Flora, various mhGAP trained members of the hospital staff voluntarily work in support, and the Bishop has assigned one of the priests to act as patron and chaplain. They have recently successfully registered the ‘Tumuka Mental Health Epicentre’ as an NGO. When we called, there were twelve people resident, all pleased to be able to talk to us about their difficulties, and the ways in which they contribute to their community.

For example, C. looks after Reception; he had been head of a secondary school before psychosis got the better of him. His parents believed this was caused by witchcraft, a spiritual attack, and took him to shrines and healers. He was hurt by his treatment, and seemed to fare little better at Butabika, the national government psychiatric hospital. Now he is improving, hopeful, life is better, and he wants to make up for lost years. B. runs weekly AA meetings at the centre, drawing on his own experience of recovering from alcoholism. Other residents have epilepsy, dementia, depression, stories of loss, mistreatment and disadvantage. Their testimonies give powerful witness to the possibility of recovering to become useful and valued members of society.

There are regular talks and activities for centre residents, who contribute what they can, but it is a hand to mouth existence. There is a flat screen TV, but not quite enough beds at the moment! Local people help with food and firewood; a supportive local leader lives close by and keeps an eye out for them. One of the nurses has opened a small pharmacy on the premises; sales of common medicines to people living nearby generate a little income.

The energy, enthusiasm and self-belief in this place is palpable. Innocent’s parting message was ‘People should not fear to start!’ Even if the task seems impossibly big, it is better to start something, somehow…

Linda Shuttleworth, 12 March 2022.